2. Development Environments & Expressions

Development Environments

Our course is based on MoonBit, a modern, statically-typed, multi-paradigm programming language with newbie-friendly lightweight syntax. To learn more about MoonBit, please visit our website.

MoonBit's development tools mainly consist of two parts: the VS Code extension and the command-line tool.

The extension is based on the widely used editor, VS Code, and provides a coding environment, a language server, and a package-level building tool. The language server provides useful features such as syntax highlighting, variable reference and definition jumping, automatic code completion, and program running and debugging. A package in MoonBit is a structure organizing multiple source files. In a package, functions defined in different source files are mutually accessible, making it easy for developers to work on various projects, especially those of a small scale.

The command-line tool provides project-level development support, including building, testing, and dependency management. A project in MoonBit typically consists of multiple mutually-dependent packages. You may also import other packages to use features implemented by other developers.

In later chapters, we will provide a detailed introduction to projects and packages. For now, we will focus on the package level.

It is worth mentioning that, VS Code offers a zero-install web-based version. Therefore, at least three types of development environments are supported: browser-based environment (e.g., VS Code for the Web), cloud-native environment (e.g., Coding, Gitpod, and GitHub.dev), and local environment. For this course, any one of them is appropriate.

Browser-Based Environment

Visit try.moonbitlang.com, or click the "Try" tab on our Website. Currently, the environment offers various features, including file creation, code execution and sharing. Besides, sample programs are provided for beginners to learn MoonBit.

Currently, this environment does not save user data, including all the files created and edited by users. Therefore, to prevent the loss of valuable code, it is highly recommended to create a local backup.

Cloud-Native Environment

Cloud-native environments are typically based on remote servers. Unlike traditional servers, they are usually not charged on a monthly basis but rather on-demand.

These servers are provided by different cloud server providers. However, the general setup procedures for a MoonBit development environment remain the same: create or clone a repository, launch the environment, and then install the "MoonBit Language" extension.

Advanced users may also install the command-line tools or clone the cloud-native development template. For further guidance, please refer to the MoonBit's Build System Tutorial.

Local Environment

To set up a local environment for MoonBit, you can begin by installing VS Code or VS Codium as the code editor. Afterwards, you can follow the same procedure as in the cloud-native environment to install the MoonBit extension and command-line tools.

Expressions

Upon setting up the development environment, let us take a look at the classic program from the preceding chapter:

// top-level function definition

fn num_water_bottles(num_bottles: Int, num_exchange: Int) -> Int {

// local function definition

fn consume(num_bottles, num_drunk) {

// conditional expression

if num_bottles >= num_exchange {

// variable binding

let num_bottles = num_bottles - num_exchange + 1

let num_drunk = num_drunk + num_exchange

// function application

consume(num_bottles, num_drunk)

} else {

num_bottles + num_drunk

}

}

consume(num_bottles, 0)

}

// test block

test {

// statements

assert_eq!(num_water_bottles(9, 3), 13)

assert_eq!(num_water_bottles(15, 4), 19)

}

In the above program, a top-level function and a test block are defined. In the top-level function, a local function is defined and invoked. The value of the local function is a conditional expression. In the true branch, two variable bindings are defined, and the local function is called; whereas in the false branch, a simple addition operation is executed. In the test block, two test commands are used to judge the correctness of our program.

Since this program does not generate any output, how exactly is it executed?

In order to write accurate programs, it is essential to understand how programs are executed. Therefore, it is necessary to establish a computational model that comprehends the process. MoonBit programs can be viewed using an expression-oriented programming approach. They are composed of expressions that represent values, and their execution involves reducing these expressions.

In contrast, imperative programming consists of statements that may modify the program's state. For example, statements may include "create a variable named x", "assign 5 to x", or "let y point to x", etc.

In the upcoming chapters, we will primarily focus on expression-oriented programming, while further information regarding imperative programming will be introduced in future chapters.

Types, Values, and Expressions

A type corresponds to a set of values. For instance, Int represents a subset of integers, Double represents a subset of real numbers, and String represents a collection of strings.

An expression consists of value-based operations and can be reduced to a value. Expressions can be nested using parentheses.

Following are some examples:

| Type | Value | Operation | Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

Int | -1 0 1 2 | + - * / | 5 (3 + y * x) |

Double | 0.12 3.1415 | + - * / | 3.0 * (4.0 * a) |

String | "hello" "Moonbit" | + | "Hello, " + "MoonBit" |

Bool | true false | && || not() | not(b1) || b2 |

Static and Dynamic Type Systems

In static type systems, type checking is performed before the program is executed, whereas in dynamic type systems, type checking occurs during program execution. In other words, the key distinction between dynamic and static type systems lies in whether the program is running or not.

MoonBit has a static type system, where its compiler performs type checking before runtime. This approach aims to minimize the likelihood of encountering runtime errors stemming from the execution of operations on incompatible data types, such as attempting arithmetic calculations on Boolean values. By conducting type checking in advance, MoonBit strives to prevent program interruptions and ensure accurate outcomes.

In MoonBit, each identifier can be associated with a unique type with a colon :. For example,

x: Inta: Doubles: String

Each MoonBit expression also has a unique type determined by its sub-expressions.

As shown, the identifier a is of type Double, so it can be added to a Double value, i.e., 0.2. After that, the to_int() function converts the sum to Int, enabling it to be added to x, which is also of type Int. Since the sequence of operations yields an integer as its final value, the expression is of type Int.

The MoonBit compiler uses type inference before runtime to ensure correct type usage, and our development tools can also detect type errors and show real-time suggestions during development.

As shown, the editor highlights type errors using red squiggly lines. In this case, the error arises from attempting to directly add a string s and a sub-expression of type Int.

Basic Data Types

To engage in expression-oriented programming with MoonBit, it is essential to understand the types of values that the language supports. This chapter will introduce basic data types, including Boolean values, integers, floating-point numbers, characters, strings, and tuples. Future chapters will delve into additional data types.

While this chapter will not explore the underlying implementation of data, such as two's complement, related materials are provided for those interested in further understanding the topic.

Boolean Values

The first data type we will introduce here is the Boolean value, also known as a logical value. It is named after the mathematician George Boole, who is credited with inventing Boolean algebra.

In MoonBit, the type for Boolean values is Bool, and it can only have two possible values: true and false. The following are three basic operations it supports:

- NOT: true becomes false, false becomes true.

- Example:

not(true) == false

- Example:

- AND: both must be true to be true.

- Example:

true && false == false

- Example:

- OR: both must be false to be false.

- Example:

true || false == true

- Example:

In MoonBit, == represents a comparison between values. In the above examples, the left-hand side is an expression, and the right-hand side is the expected result. In other words, these examples themselves are expressions of type Bool, and we expect their values to be true.

The || and && operators are short-circuited. This means that if the outcome of the entire expression can be determined, the calculation will be halted, and the result will be immediately returned. For instance, in the case of true || ..., it is evident that true || any value will always yield true. Therefore, only the left side of the || operator needs to be evaluated. Similarly, when evaluating false && ..., since it is known that false && any value will always be false, the right side is not evaluated either. In this case, if the right side of the operator contains side effects, those side effects may not occur.

Quiz: How to define XOR (true if only one is true) using OR, AND, and NOT?

Integers

In mathematics, the set of integers is denoted as

In MoonBit, there are two integer types, each with a different range:

- Integer

Int: ranging fromto - Long integer

Int64: ranging fromto

When dividing two integers in MoonBit, the result is still an integer, representing the quotient. If the division involves negative integers, the operation is performed on their absolute values, and then a negative sign may be assigned to the result. For instance, when dividing

Since integers have a limited range, performing operations that exceed this range can lead to an overflow. In such cases, the result will still be a value within the range, but it may not be the expected result. For example,

In MoonBit, integers can only perform arithmetic operations with integers, and long integers can only perform arithmetic operations with long integers. However, we can use to_int64() or to_int() to perform type conversion. Besides, when we need to define an Int64 literal, we can use the suffix L to distinguish it from an Int literal.

It is important to note that if we need to call a function on an integer, we must wrap it in parentheses. For example, (100).to_int64() will convert Int to Int64.

Quiz: How to get the average of two positive Int values? Be cautious of overflow!

Floating-Point Numbers

Just like integers have a limited range, computers can only represent finite decimals of floating-point numbers and approximate their values. Internally, they are represented as 0.1 + 0.2 != 0.3.

In MoonBit, the floating-point type is double-precision: Double. It cannot be mixed with other types in calculations. Therefore, -1.2 + 1 will result in an error. As a solution, we can either use (1).to_double() to convert 1 from Int to Double, or use (-1.2).to_int() to convert -1.2 from Double to Int. The latter will round off the decimal part of the floating point number, so -1.2 will be converted to -1.

Quiz: How to compare 0.1 + 0.2 with 0.3 using Int and Double conversions?

Characters and Strings

Roughly speaking, in computer science, the term "characters" refers to various symbols and graphemes, including letters, numbers, East Asian ideographs, and other graphical elements. On the other hand, "strings" are sequences of characters.

In MoonBit, the character type is represented by Char and its literals are enclosed in single quotes, e.g., 'a'. The string type is represented by String and its literals are enclosed in double quotes, e.g., "Hello!".

In computer science, characters are mapped to numbers through encoding. Various encoding schemes have been used throughout history, and even within the same period, different encoding schemes may be employed in different occasions. One of the most commonly used encoding scheme is the American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) released in 1963. ASCII defines the mapping of Latin characters and common symbols to the range of 0 to 127. For instance, the capital letters 'A' to 'Z' correspond to the numbers 65 to 90.

Subsequently, Unicode was introduced with multiple variants like UTF-8 and UTF-16. It has expanded upon the ASCII standard by incorporating characters from other writing systems. For example, in Unicode, the Chinese characters "月" and "兔" correspond to the numbers 26376 and 20820, respectively.

MoonBit's internal character encoding scheme is UTF-16, based on which we can perform type conversion between characters and integers. For example, Char::from_int(65) results in 'A'.

It is important to note that each character in MoonBit corresponds strictly to a code unit of UTF-16. Therefore, "MoonBit月兔".get(7) == '月' because the character '月' corresponds to a single code unit, while "🌕".length() == 2 since the character '🌕' has two code units.

Tuples

Sometimes, it is necessary to represent data types that combine multiple pieces of information. For instance, a date can be represented by three numbers, and a person's personal information may include their name and age. In such cases, tuples can be used to combine data of different types with a fixed length. Tuples allow us to group together multiple values into a single entity.

(2023, 10, 24): (Int, Int, Int)("Bob", 3): (String, Int)

We can access the data by using zero-based indexing.

(2023, 10, 24).0 == 2023(2023, 10, 24).1 == 10

Unit

In MoonBit, the Unit type represents a singular value denoted as (). Though seemingly useless, it holds significant implications as it enables the treatment of statements as expressions: in MoonBit, all statements evaluate to ().

Other Data Types

MoonBit has a rich type system, which includes many other types that we have not yet discussed, such as function types and list types. These types will be explored in detail in future chapters.

Expression Evaluation

Reduction vs Execution

MoonBit expressions can be seen as a way of representing values, and its evaluation can be seen as a series of computations or reductions. In contrast, imperative programming can be seen as executing a series of actions or commands, where each command modifies the state of the machine, e.g.,

- Create pointers

xandyand allocate memory, setxto 3, setyto 4. - Set

yto point tox. - Increment

x.

We can denote the reduction of an

(the reduction result of a value is itself)

Also, we can break down the process of decomposition

Therefore,

Variable Binding

In MoonBit, variable binding can be achieved using the syntax let <identifier> : <type> = <expression>. It assigns an identifier to a value that is represented by an expression. In many cases, the type declaration is optional as the compiler can infer it based on the type of the expression.

let x = 10let y = "String"

Rebinding an identifier in MoonBit will result in shadowing the previous value associated with that identifier, rather than modifying it. This means that the new value assigned to the identifier will take precedence over the previous value within the scope where it is rebound.

By utilizing variable binding effectively, you can avoid complex nesting of expressions and make the code more readable and maintainable.

Expression Blocks and Scope

In MoonBit, expression blocks can be defined using the syntax

{

Variable bindings

Variable bindings

……

Expression

}

The type/value of an expression block is the type/value of the last expression.

When a function or identifier is defined outside of any expression block, it is called a top-level definition. Conversely, when a function or identifier is defined within an expression, it is referred to as a local definition.

The terms "top-level" and "local" are used to describe the scope in which these definitions are effective. Top-level definitions have a global scope, meaning they are valid throughout the entire file, while local definitions have a limited scope, starting from the point of definition and ending at the completion of the enclosing expression block.

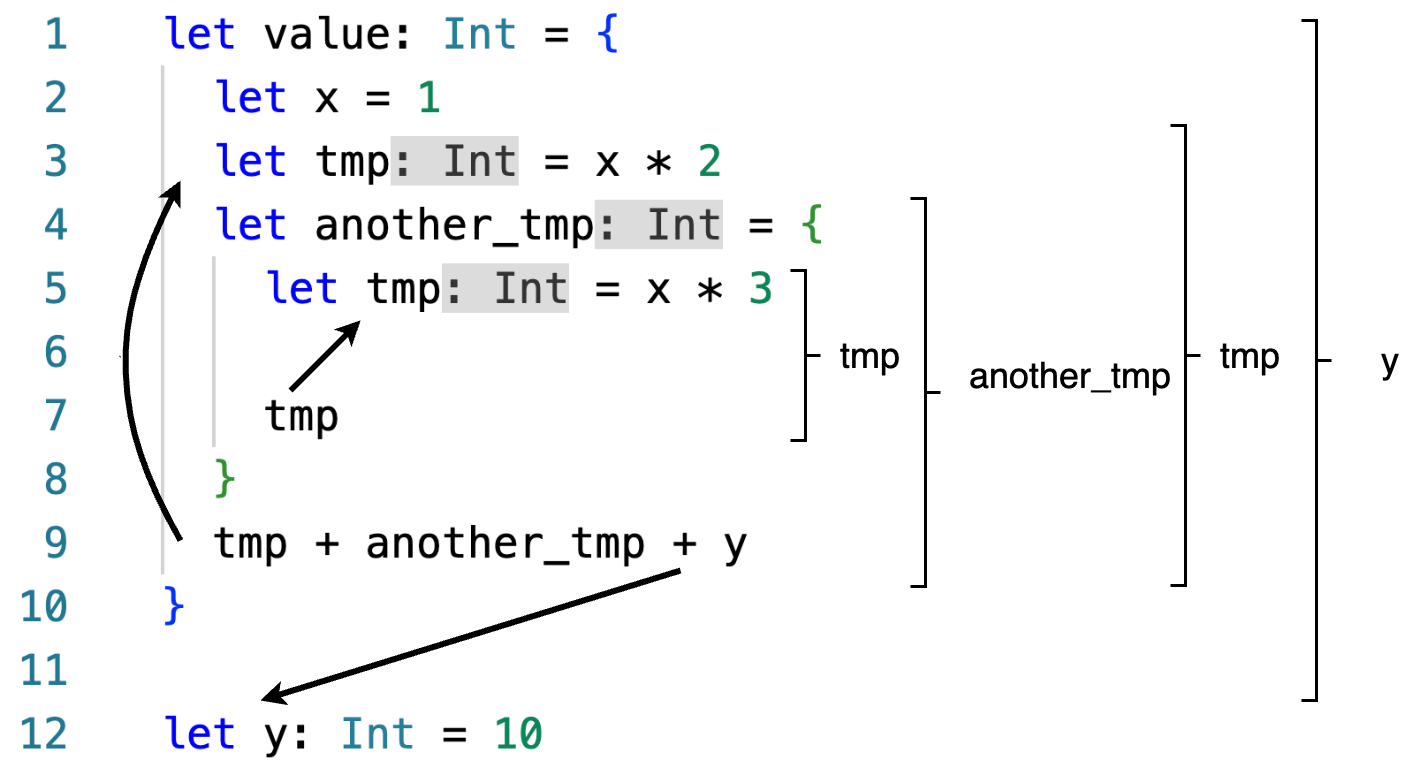

For example, in the above figure, we have defined two top-level identifiers: value and y. The value of value is determined by the expression block, which includes the bindings of x, tmp, and another_tmp. In another_tmp, we have another binding of tmp.

It is important to note the direction of the arrows. On line 7, the tmp refers to the most recent definition of tmp on line 5, overshadowing the definition on line 3. However, on line 9, tmp refers to the definition on line 3, as it is now outside the scope of the tmp defined on line 5.

Expression Reduction under Variable Binding

Expression reduction can be broken down into the following steps:

- Reduce the expression on the right-hand side of the variable binding.

- Replace occurrences of identifiers with their reduction results.

- Omit the variable binding part.

- Reduce the remaining expressions.

Take the following code snippet as an example:

let value: Int = {

let x = 1

let tmp = x * 2

let another_tmp = {

let tmp = x * 3

tmp

}

tmp + another_tmp + y

}

let y: Int = 10

First, we can replace all occurrences of x and y with their values, thereby omitting their variable bindings.

let value: Int = {

// Omit the variable binding of x

let tmp = 1 * 2 // Replace x

let another_tmp = {

let tmp = 1 * 3 // Replace x

tmp

}

tmp + another_tmp + 10 // Replace y

}

// Omit the variable binding of y

Then, we can reduce the expression for two variable bindings of tmp, and replace the occurrences of tmp in the expression block of the variable binding of another_tmp.

let value: Int = {

let tmp = 2 // Reduce the expression on the right-hand side

let another_tmp = {

let tmp = 3 // Reduce the expression on the right-hand side

3 // Replace tmp

}

tmp + another_tmp + 10

}

After that, we can now compute the value of another_tmp, which is determined by the last expression in the expression block.

let value: Int = {

let tmp = 2

let another_tmp = 3 // Reduce the expression on the right-hand side

tmp + another_tmp + 10

}

Thus, the remaining occurrences of identifiers in the expression block of value can also be replaced with their values.

let value: Int = {

let tmp = 2

let another_tmp = 3

2 + 3 + 10

}

Finally, we get the value of value.

let value: Int = 15

Conditional Expression

Conditional expressions enable you to obtain different values based on specified logical conditions.

In MoonBit, its syntax is:

if condition

expression block|if condition is true

else

expression block|if condition is false

In MoonBit, conditional expressions are also expressions and can be used within other expressions. For example,

( if 1 < 100 { 1 } else { 0 } ) * 10( if x > y { "x" } else { "y" } ) + " is bigger"if 0.1 + 0.2 == 0.3 { "Great!" } else { "C'est la vie :-)" }

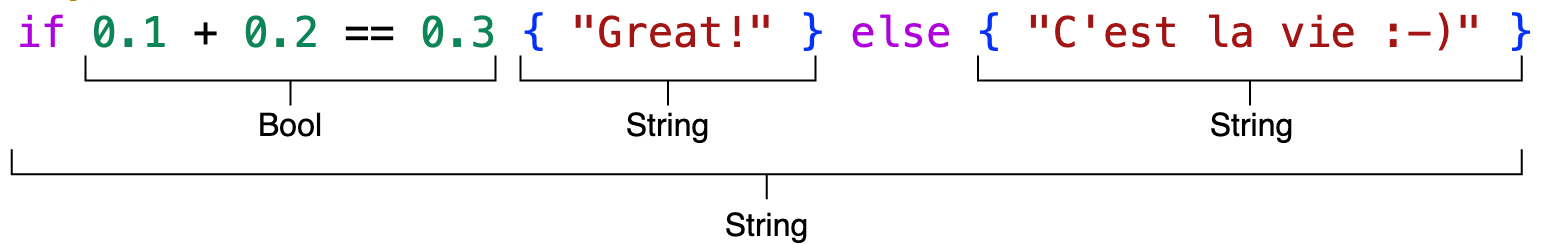

Expression blocks in branches must have the same type, and the type of the entire conditional expression is determined by the type of an expression block from these branches. The type of the condition must be a Boolean.

In the above conditional expression, the condition is a Bool expression to check the equality of two floating-point numbers; the values of the two branches are both of type String, so the entire expression is also of type String.

The value of a conditional expression depends on the reduction result of the condition being true or false. For example,

If the true branch ends with a statement, the false branch can be omitted. Implicitly, there is a hidden false branch returning (), and therefore the two branches still have the same type, i.e., Unit.

Summary

In this chapter, we learned:

- How to set up the MoonBit development environment

- Browser-based environment

- Cloud-native environment

- Local environment

- MoonBit basic data types

- Boolean values

- Integers and floating-point numbers

- Characters and strings

- Tuples

- How to view MoonBit programs in terms of expressions and values, and understand the execution of MoonBit programs by reduction.