6. Generics & Higher-Order Functions

In development, we often encounter similar data structures and similar operations. At such times, we can reuse this information through good abstraction, which not only ensures maintainability but also allows us to ignore some details. Good abstraction should follow two principles: first, it represents same patterns or structures that appear repeatedly in the code; second, it has appropriate semantics. For example, we might need to perform the sum operation on lists of integers on many occasions, hence the repetition. Since summing has appropriate semantics, it is suitable for abstraction. We abstract this operation into a function and then use the function repeatedly, instead of writing the same code.

Programming languages provide us with various means of abstraction, such as functions, generics, higher-order functions, interfaces, etc. This chapter will introduce generics and higher-order functions, and the next chapter will discuss interfaces.

Generic Functions and Generic Data

Let's first look at the stack data structure to understand why and how we use generics.

A stack is a collection composed of a series of objects, where the insertion and removal of these objects follow the Last-In-First-Out (LIFO) principle. For example, consider the containers stacked on a ship as shown in the left-hand image below.

Clearly, new containers are stacked on top, and when removing containers, those on top are removed first, meaning the last placed container is the first to be removed. Similarly, with a pile of stones in the right-hand image, if you don’t want to topple the pile, you can only add stones at the top or remove the most recently added stones. This structure is a stack. There are many such examples in our daily lives, but we will not enumerate them all here.

For a data type stack, we can define operations as follows. Taking an integer stack IntStack as an example, we can create a new empty stack; we can add an integer to the stack; we can try to remove an element from the stack, which may not exist because the stack could be empty, hence we use an Option to wrap it.

empty: () -> IntStack // create a new stack

push : (Int, IntStack) -> IntStack // add a new element to the top of the stack

pop: IntStack -> (Option[Int], IntStack) // remove an element from the stack

As shown in the diagram below, we add a 2 and then remove a 2. We simply implement this definition of a stack.

enum IntStack {

Empty

NonEmpty(Int, IntStack)

}

fn IntStack::empty() -> IntStack { Empty }

fn push(self: IntStack, value: Int) -> IntStack { NonEmpty(value, self) }

fn pop(self: IntStack) -> (Option[Int], IntStack) {

match self {

Empty => (None, Empty)

NonEmpty(top, rest) => (Some(top), rest)

}

}

In the code snippet, we see that we set the first argument as IntStack, and the variable name is self, allowing us to chain function calls. This means we can write IntStack::empty().push(2).pop() instead of pop(push(2, IntStack::empty())). The deeper meaning of this syntax will be explained in the next chapter.

Returning to our code, we defined a recursive data structure based on stack operations: a stack may be empty or may consist of an element and a stack. Creating a stack is to build an empty one. Adding an element builds a non-empty stack with the top element being the one we want to add, while the stack underneath remains as it was. Removing from the stack requires pattern matching, where if the stack is empty, there are no values to retrieve; if the stack is not empty, the top element can be taken.

The definition of a stack is very similar to that of a list. In fact, in MoonBit built-in library, lists are essentially stacks.

After defining a stack for integers, we might also want to define stacks for other types, such as a stack of strings. This is simple, and we only demonstrate the code here without explanation.

enum StringStack {

Empty

NonEmpty(String, StringStack)

}

fn StringStack::empty() -> StringStack { Empty }

fn push(self: StringStack, value: String) -> StringStack { NonEmpty(value, self) }

fn pop(self: StringStack) -> (Option[String], StringStack) {

match self {

Empty => (None, Empty)

NonEmpty(top, rest) => (Some(top), rest)

}

}

Indeed, the stack of strings looks exactly like the stack of integers, except for some differences in type definitions. But if we want to add more data types, should we redefine a stack data structure for each type? Clearly, this is unacceptable.

Generics in MoonBit

Therefore, MoonBit provides an important language feature: generics. Generics are about taking types as parameters, allowing us to define more abstract and reusable data structures and functions. For example, with our stack, we can add a type parameter T after the name to indicate the actual data type stored.

enum Stack[T] {

Empty

NonEmpty(T, Stack[T])

}

fn Stack::empty[T]() -> Stack[T] { Empty }

fn push[T](self: Stack[T], value: T) -> Stack[T] { NonEmpty(value, self) }

fn pop[T](self: Stack[T]) -> (Option[T], Stack[T]) {

match self {

Empty => (None, Empty)

NonEmpty(top, rest) => (Some(top), rest)

}

}

Similarly, the functions defined later also have a T as a type parameter, representing the data type stored in the stack we operate on and the type of data we want to add. We only need to replace the identifier with a parameter, replacing T with a specific type, to obtain the actual data structures and functions. For example, if T is replaced with Int, then we obtain the previously defined IntStack.

Example: Generic Pair

We have already introduced the syntax, and we have more examples.

struct Pair[A, B]{ first: A; second: B }

fn identity[A](value: A) -> A { value }

For example, we can define a pair of data, or a tuple. The pair has two type parameters because we might have two elements of two different types. The stored values first and second are respectively of these two types. As another example, we define a function identity that can operate on any type and always return the input value.

Stack and Pair can themselves be considered as functions on types, with their parameters being T or A, B, and the results of the operation are specific types like Stack[T] and Pair[A, B]. Stack and Pair can be regarded as type constructors. In most cases, the type parameters in MoonBit can be inferred based on the specific parameter types.

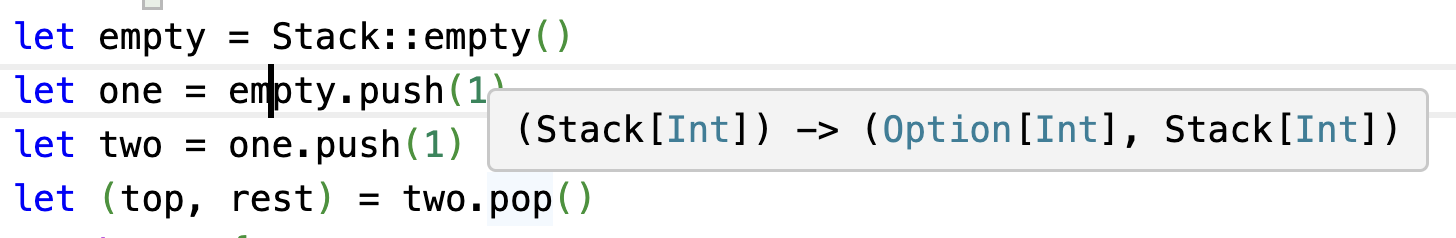

For example, in the screenshot here, the type of empty is initially unknown. But after push(1), we understand that it is used to hold integers, thus we can infer that the type parameters for push and empty should be integer Int.

Example: Generic Functional Queue

Now let's look at another generic data structure: the queue. We have already used the queue in the breadth-first sorting in the last lesson. Recall, a queue is a First-In-First-Out data structure, just like we queue up in everyday life. Here we define the following operations, where the queue is called Queue, and it has a type parameter.

fn empty[T]() -> Queue[T] // Create an empty queue

fn push[T](q: Queue[T], x: T) -> Queue[T] // Add an element to the tail of the queue

// Try to dequeue an element and return the remaining queue; if empty, return itself

fn pop[T](q: Queue[T]) -> (Option[T], Queue[T])

Every operation has a type parameter, indicating the type of data it holds. We define three operations similar to those of a stack. The difference is that when removing elements, the element that was first added to the queue will be removed.

The implementation of the queue can be simulated by a list or a stack. We add elements at the end of the list, i.e., at the bottom of the stack, and take them from the front of the list, i.e., the top of the stack. The removal operation is very quick because it only requires one pattern matching. But adding elements requires rebuilding the entire list or stack.

Cons(1, Cons(2, Nil)) => Cons(1, Cons(2, Cons(3, Nil)))

As shown here, to add an element at the end, i.e., to replace Nil with Cons(3, Nil), we need to replace the whole Cons(2, Nil) with Cons(2, Cons(3, Nil)). And worse, the next step is to replace the [2] occurred as tail in the original list with [2, 3], which means to rebuild the entire list from scratch. It is very inefficient.

To solve this problem, we use two stacks to simulate a queue.

struct Queue[T] {

front: Stack[T] // For removing elements

back: Stack[T] // For storing elements

}

One stack is for the removal operation, and the other for storage. In the definition, both types are Stack[T], and T is the queue's type parameter. When adding data, we directly store it in back: this step is quick because it builds a new structure on top of the original one; the removal operation also only needs one pattern matching, which is not slow either. When all elements in front have been removed, we need to rotate all elements from back into front. We check this after each operation to ensure that as long as the queue is not empty, then front is not empty. This checking is the invariant of our queue operations, a condition that must hold. This rotation is very costly, proportional to the length of the list at that time, but the good news is that this cost can be amortized, because after a rotation, the following several removal operations no longer need rotation.

Let's look at a specific example. Initially, we have an empty queue, so both stacks are empty. After one addition, we add a number to back. Then we organize the queue and find that the queue is not empty, but front is empty, which does not meet our previously stated invariant, so we rotate the stack back and move rotated elements to front. Afterwards, we continue to add elements to back. Since front is not empty, it meets the invariant, and we do not need additional processing.

After that, our repeatedly additions are only the quick addition of new elements in back. Then, we remove elements from front. We check the invariant after the operation. We find that the queue is not empty, but front is empty, so we do retate back and move elements to front again. After that, we can normally take elements from front.

You can see that one rotation supports multiple removal operations, therefore the overall cost is much less than rebuilding the list every time.

struct Queue[T] {

front: Stack[T]

back: Stack[T]

}

fn Queue::empty[T]() -> Queue[T] { {front: Empty, back: Empty} }

// Store element at the end of the queue

fn push[T](self: Queue[T], value: T) -> Queue[T] {

normalize({ ..self, back: self.back.push(value)}) // By defining the first argument as self, we can use xxx.f()

}

// Remove the first element

fn pop[T](self: Queue[T]) -> (Option[T], Queue[T]) {

match self.front {

Empty => (None, self)

NonEmpty(top, rest) => (Some(top), normalize({ ..self, front: rest}))

}

}

// If front is empty, reverse back to front

fn normalize[T](self: Queue[T]) -> Queue[T] {

match self.front {

Empty => { front: self.back.reverse(), back: Empty }

_ => self

}

}

// Helper function: reverse the stack

fn reverse[T](self: Stack[T]) -> Stack[T] {

fn go(acc, xs: Stack[T]) {

match xs {

Empty => acc

NonEmpty(top, rest) => go((NonEmpty(top, acc) : Stack[T]), rest)

}

}

go(Empty, self)

}

Here is the code for the queue. You can see that we extensively apply generics, so our queue can contain any type, including queues containing other elements. The functions here are the specific implementations of the algorithm we just explained. In function push, you we called the stack's push function through back.push(). We will explain this specifically in the next lesson.

Higher-Order Functions

This section continues to focus on how to use the features provided by MoonBit to reduce repetitive code and enhance code reusability. So, let’s start with an example.

fn sum(list: @immut/list.T[Int]) -> Int {

match list {

Nil => 0

Cons(hd, tl) => hd + sum(tl)

}

}

Consider some operations on lists. For instance, to sum an integer list, we use structural recursion with the following code: if empty, the sum is 0; otherwise, the sum is the current value plus the sum of the remaining list elements.

fn length[T](list: @immut/list.T[T]) -> Int {

match list {

Nil => 0

Cons(hd, tl) => 1 + length(tl)

}

}

Similarly, to find the length of a list of any data type, using structural recursion, we write: if empty, the length is 0; otherwise, the length is 1 plus the length of the remaining list.

Notice that these two structures have considerable similarities: both are structural recursions with a default value when empty, and when not empty, they both involve processing the current value and combining it with the recursive result of the remaining list. In the summing case, the default value is 0, and the binary operation is additio; in the length case, the default value is also 0, and the binary operation is to replace the current value with 1 and then add it to the remaining result. How can we reuse this structure? We can write it as a function, passing the default value and the binary operation as parameters.

First-Class Function in MoonBit

This brings us to the point that in MoonBit, functions are first-class citizens. This means that functions can be passed as parameters and can also be stored as results. For instance, the structure we just described can be defined as the function shown below, where f is passed as a parameter and used in line four for calculation.

fn fold_right[A, B](list: @immut/list.T[A], f: (A, B) -> B, b: B) -> B {

match list {

Nil => b

Cons(hd, tl) => f(hd, fold_right(tl, f, b))

}

}

Here’s another example. If we want to repeat a function’s operation, we could define repeat as shown in the first line. repeat accepts a function as a parameter and then returns a function as a result. Its operation results in a function that calculates the original function twice.

fn repeat[A](f: (A) -> A) -> (A) -> A {

fn (a) { f(f(a)) } // Return a function as a result

}

fn plus_one(i: Int) -> Int { i + 1 }

fn plus_two(i: Int) -> Int { i + 2 }

let add_two: (Int) -> Int = repeat(plus_one) // Store a function

let compare: Bool = add_two(2) == plus_two(2) // true (both are 4)

For example, if we have two functions plus_one and plus_two, by using repeat with plus_one as a parameter, the result is a function that adds one twice, i.e., adds two. We use let to bind this function to add_two, then perform calculations using normal function syntax to get the result.

let add_two: (Int) -> Int = repeat(plus_one)

repeat(plus_one)

fn (a) { plus_one(plus_one(a)) }

let x: Int = add_two(2)

add_two(2)

plus_one(plus_one(2))

plus_one(2) + 1

(2 + 1) + 1

3 + 1

4

Let's explore the simplification here. First, add_two is bound to repeat(plus_one). For this line, simplification is about to replace identifiers in expressions with arguments, obtaining a function as a result. Now, we cannot simplify further for this expression. Then, we Calculate add_two(2). Similarly, we replace identifiers in the expression and simplify plus_one. After more simplifications, we finally obtain our result, 4.

We've previously mentioned function types, which go from the accepted parameters to the output parameters, where the accepted parameters are enclosed in parentheses.

(Int) -> IntIntegers to integers(Int) -> (Int) -> IntIntegers to a function that accepts integers and returns integers(Int) -> ((Int) -> Int)The same as the previous line((Int) -> Int) -> IntA function that accepts a function from integers to integers and returns an integer

For example, the function type from integer to integer, would be (Int) -> Int. The second line shows an example from integer to function. Notice that the function’s parameter also needs to be enclosed in parentheses. The function type is actually equivalent to enclosing the entire following function type in parentheses, as seen in the third line. If it's from function to integer, as we mentioned earlier, the accepted parameter needs to be enclosed in parentheses, so it should look like the fourth line, not the second.

Example: Fold Functions

Here are a few more common applications of higher-order functions. Higher-order functions are functions that accept functions. fold_right, which we just saw, is a common example. Below, we draw its expression tree.

fn fold_right[A, B](list: @immut/list.T[A], f: (A, B) -> B, b: B) -> B {

match list {

Nil => b

Cons(hd, tl) => f(hd, fold_right(tl, f, b))

}

}

You can see that for a list from 1 to 3, f is applied to the current element and the result of the remaining elements each time, thus it looks like we're building a fold from right to left, one by one, to finally get a result. Therefore, this function is called fold_right. If we change the direction, folding the list from left to right, then we get fold_left.

fn fold_left[A, B](list: @immut/list.T[A], f: (B, A) -> B, b: B) -> B {

match list {

Nil => b

Cons(hd, tl) => fold_left(tl, f, f(b, hd))

}

}

Here, we only need to swap the order, first processing the current element with the previous accumulated result, then incorporating the processed result into the subsequent processing, as shown in the fourth line. This function folds from left to right.

Example: Map Function

Another common application of higher-order functions is to map each element of a function.

struct PersonalInfo { name: String; age: Int }

fn map[A, B](self: @immut/list.T[A], f: (A) -> B) -> @immut/list.T[B] {

match list {

Nil => Nil

Cons(hd, tl) => Cons(f(hd), map(tl, f))

}

}

let infos: @immut/list.T[PersonalInfo] = ???

let names: @immut/list.T[String] = infos.map(fn (info) { info.name })

For example, if we have some people's information and we only need their names, then we can use the mapping function map, which accepts f as a parameter, to map each element in the list one by one, finally obtaining a new list where the type of elements has become B. This function's implementation is very simple. What we need is also structural recursion. The last application is as shown in line 8. Maybe you feel like you've seen this map structure before: structural recursion, a default value for the empty case, and a binary operation processing the current value combined with the recursive result when not empty. Indeed, map can be entirely implemented using fold_right, where the default value is an empty list, and the binary operation is the Cons constructor.

fn map[A, B](list: @immut/list.T[A], f: (A) -> B) -> @immut/list.T[B] {

fold_right(list, fn (value, cumulator) { Cons(f(value), cumulator) }, Nil)

}

Here we leave you an exercise: how to implement fold_left with fold_right? Hint: something called Continuation may be involved. Continuation represents the remaining computation after the current operation, generally a function whose parameter is the current value and whose return value is the overall program's result.

Having learned about generics and higher-order functions, we can now define the binary search tree studied in the last lesson as a more general binary search tree, capable of storing various data types, not just integers.

enum Tree[T] {

Empty

Node(T, Tree[T], Tree[T])

}

// We need a comparison function to determine the order of values

// The comparison function should return an integer representing the comparison result

// -1: less than; 0: equal to; 1: greater than

fn insert[T](self: Tree[T], value: T, compare: (T, T) -> Int) -> Tree[T]

fn delete[T](self: Tree[T], value: T, compare: (T, T) -> Int) -> Tree[T]

Here, the data structure itself accepts a type parameter to represent the data type it stores. Considering that a binary search tree should be ordered, we need to know how to sort this specific type, hence we accept a comparison function as a parameter, which should return an integer representing the comparison result as less than, equal to, or greater than, as the code shows. Indeed, we could completely use another feature of MoonBit to omit this parameter. We will introduce this in the next lesson.

Summary

In this chapter, we introduced the concepts of generics and functions as first-class citizens, and we saw how to use them in MoonBit. We also discussed the implementations of the data structures stack and queue.

For further exploration, please refer to:

- Software Foundations, Volume 1: Logical Foundations: Poly; or

- Programming Language Foundations in Agda: Lists