8. Queues

Queues are a fundamental data structure in computer science, following the First-In-First-Out (FIFO) principle, meaning the first element added to the queue will be the first one to be removed. The chapter will explore two primary methods of implementing queues: circular queues and singly linked lists. Additionally, it will also introduce tail calls and tail recursion, which are essential for optimizing recursive functions.

Basic Operations

A queue should support the following basic operations:

struct Queue { .. }

fn make() -> Queue // Creates an empty queue.

fn push(self: Queue, t: Int) -> Queue // Adds an integer element to the queue.

fn pop(self: Queue) -> Queue // Removes an element from the queue.

fn peek(self: Queue) -> Int // Views the front element of the queue.

fn length(self: Queue) -> Int // Obtains the length of the queue.

The pop and push operations will directly modify the original queue. For convenience, we also return the modified queue, so that we can easily make chain calls.

make().push(1).push(2).push(3).pop().pop().length() // 1

Circular Queues

Circular queues are usually implemented using arrays, which provide a continuous storage space where each position can be modified. Once an array is allocated, its length remains fixed.

The following code snippet shows the basic usage of the built-in Array in MoonBit. It is worth noting that its index starts from 0, and we will later learn the benefits of doing so.

let a: Array[Int] = Array::make(5, 0)

a[0] = 1

a[1] = 2

println(a) // Output: [1, 2, 0, 0, 0]

When implementing a circular queue, we keep track of the start and end indices. Whenever a new element is pushed, we move the end index one step forward. The pop operation clears the element at the position of start and moves it one step forward. If the index exceeds the length of the array, we wrap it back to the beginning.

The following diagram is a demonstration of these operations. First, we create an empty queue by calling make(). At this point, the start and end indices both point to the first element. Then, we push an element into the queue by calling push(1). The element 1 is then added to the position pointed to by end, and the end index is updated. Afterwards, we call push(2) to push another element into the queue, and finally call pop() to pop out the first element we have pushed.

Now, let's take a look at another situation when we are close to the end of the array. At this point, end points to the position of the last element of the array. When we push an element, end cannot move forward, so we wrap it back to the beginning of the array. Then, we perform two pop operations. Similarly, when start exceeds the length of the array, it returns to the beginning of the list.

With the above basic ideas in mind, we can easily define the Queue struct and implement the push operation as follows:

struct Queue {

mut array: Array[Int]

mut start: Int

mut end: Int // end points to the empty position at the end of the queue

mut length: Int

}

fn push(self: Queue, t: Int) -> Queue {

self.array[self.end] = t

self.end = (self.end + 1) % self.array.length() // wrap around to the start of the array if beyond the end

self.length = self.length + 1

self

}

Now, we can easily see the benefit of using 0 as the starting index of an array: we can conveniently achieve the "circular" effect with the % operation.

However, the above implementation has a potential issue, which is that the number of elements in the queue may exceed the length of the array. When we know the upper limit of the number of elements, we can avoid this issue by defining an array that is long enough. If we cannot know the upper limit in advance, we can "expand" the array by replacing it with a longer array. A sample implementation is as follows:

fn _push(self: Queue, t: Int) -> Queue {

if self.length == self.array.length() {

let new_array: Array[Int] = Array::make(self.array.length() * 2, 0)

let mut i = 0

while i < self.array.length() {

new_array[i] = self.array[(self.start + i) % self.array.length()]

i = i + 1

}

self.start = 0

self.end = self.array.length()

self.array = new_array

}

self.push(t)

}

When we pop out an element, we remove the element pointed to by start, move start forward, and update the length.

fn pop(self: Queue) -> Queue {

self.array[self.start] = 0

self.start = (self.start + 1) % self.array.length()

self.length = self.length - 1

self

}

The length function simply returns the current length field of the queue, since it is dynamically maintained.

fn length(self: Queue) -> Int {

self.length

}

Generic Circular Queues

Sometimes, we may want the elements in the queue to be of a type other than Int. With MoonBit's generic mechanism, we can easily define a generic version of the Queue struct.

struct Queue[T] {

mut array: Array[T]

mut start: Int

mut end: Int // end points to the empty position at the end of the queue

mut length: Int

}

However, when implementing the make operation, how do we specify the initial value for the array? There are two options: one is to wrap the values with Option and use Option::None as the initial value; the other option is to use the default value of the type itself. How to define and utilize this default value will be discussed in Chapter 9.

fn make[T]() -> Queue[T] {

{

array: Array::make(5, T::default()), // Initialize the array with the default value of the type

start: 0,

end: 0,

length: 0

}

}

Singly Linked Lists

Singly linked lists are composed of nodes, where each node contains a value and a mutable reference to the next node.

Node[T] is a generic struct that represents a node in a linked list. It has two fields: val and next. The val field is used to store the value of the node, and its type is T, which can be any valid data type. The next field represents the reference to the next node in the linked list. It is an optional field that can either hold a reference to the next node or be empty (None), indicating the end of the linked list.

struct Node[T] {

val : T

mut next : Option[Node[T]]

}

LinkedList[T] is a generic struct that represents a linked list. It has two mutable fields: head and tail. The head field represents the reference to the first node (head) of the linked list and is initially set to None when the linked list is empty. The tail field represents the reference to the last node (tail) of the linked list and is also initially set to None. The presence of the tail field allows for efficient appending of new nodes to the end of the linked list.

struct LinkedList[T] {

mut head : Option[Node[T]]

mut tail : Option[Node[T]]

}

The implementation of make is trivial:

fn LinkedList::make[T]() -> LinkedList[T] {

{ head: None, tail: None }

}

When we push elements, we first check whether the linked list is empty. If not, add it to the end of the queue and maintain the linked list relationship.

fn push[T](self: LinkedList[T], value: T) -> LinkedList[T] {

let node = { val: value, next: None }

match self.tail {

None => {

self.head = Some(node)

self.tail = Some(node)

}

Some(n) => {

n.next = Some(node)

self.tail = Some(node)

}

}

self

}

The following diagram is a simple demonstration. When we create a linked list by calling make(), both the head and tail are empty. When we push an element using push(1), we create a new node and point both the head and tail to this node. When we push more elements, say push(2) and then push(3), we need to update the next field of the current tail node to point to the new node. The tail node of the linked list should always point to the latest node.

To get the length of the list, we can either record it in the struct as we did for circular queues, or we can use a naive recursive function to calculate it.

fn length[T](self : LinkedList[T]) -> Int {

fn aux(node : Option[Node[T]]) -> Int {

match node {

None => 0

Some(node) => 1 + aux(node.next)

}

}

aux(self.head)

}

Stack Overflow

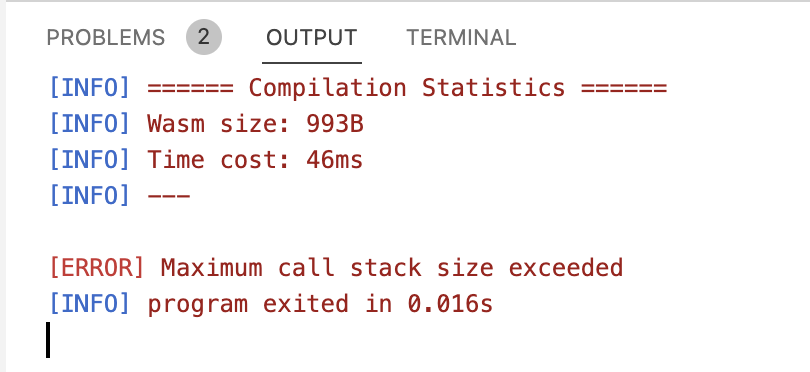

However, if the list is too long, the above implementation may lead to a stack overflow.

fn init {

let list = make()

let mut i = 0

while i < 100000 {

let _ = list.push(i)

i += 1

}

println(list.length())

}

The cause of a stack overflow is that, whenever we call a function recursively, the data (or environments) waiting to be calculated in the current layer of function call is temporarily saved in a memory space called the "stack". When we return to the current layer from a deeper recursion, the data saved in the stack space will be recovered to continue the calculation of the current function. In our case, each time we call aux recursively, we will store the information for the partial expression 1 + ... in the stack space, so that we can continue the calculation after we returned from the recursive calls.

However, the size of the stack space is limited. Therefore, if we store data on the stack every time we recurse, the stack will overflow as long as the number of recursive layers is large enough.

Taill Calls and Tail Recursion

To avoid the stack overflow issues, we can rewrite recursive functions as loops to avoid using stack space. Alternatively, we can adjust the recursive function's implementation so that each recursion does not need to preserve any environment on the stack. To achieve this, we need to ensure that the last operation of a function is a function call, known as a tail call. And if the last operation is a recursive call to the function itself, it is called tail recursion. Since the result of the function call is the final result of the computation, we don't need to preserve the current computation environment.

As shown in the code below, we can rewrite the length function to make it tail recursive:

fn length_[T](self: LinkedList[T]) -> Int {

fn aux2(node: Option[Node[T]], cumul: Int) -> Int {

match node {

None => cumul

Some(node) => aux2(node.next, 1 + cumul)

}

}

// tail recursive

aux2(self.head, 0)

}

The optimized length_ function uses tail recursion to calculate the length of the linked list without risking a stack overflow. The aux2 function uses an accumulator cumul to keep track of the length as it traverses the list. The last function call in each iteration is aux2 itself, so we can call it recursively as many times as we want without encountering a stack overflow issue.

Summary

This chapter covers the design and implementation of two basic types of queues, i.e., circular queues and singly linked lists. It also highlights the importance of understanding and utilizing tail calls and tail recursion to optimize recursive functions and prevent stack overflow, ultimately leading to more efficient and stable program performance.