7. Imperative Programming

Functional vs Imperative Programming

In the previous chapters, we used the functional programming paradigm, where the same input always produces the same output. Functional programs typically exhibit the property of referential transparency. That is, we can replace a function call with its result without changing the program's behavior.

Consider the example below. We can declare a variable x and assign it the result of an expression, like 1 + 1. This is straightforward and mirrors what we do in mathematics. We can also define a function square that takes an integer and returns its square. When we call square(x), we get the result 4, just like if we replaced square(x) with { 2 * 2 }.

let x: Int = 1 + 1 // x can be directly replaced with 2

fn square(x: Int) -> Int { x * x };

let z: Int = square(x) // can be replaced with { 2 * 2 }, still resulting in 4

However, in the real world, we often need our programs to do more than just calculations. We might need them to read from a file, write to the screen, or change data in memory. These actions are called "side effects," and they can make our programs behave differently each time they run, even with the same input. This breaks the referential transparency, making our programs harder to understand and predict.

In this chapter, we will learn the basic concepts of imperative programming. It is a paradigm of programming where we give the computer a set of commands to execute, much like giving instructions to a person. It's about telling the computer exactly what to do, step by step. This is different from functional programming, where you define what you want in terms of mathematical functions.

Commands and Side Effects

In MoonBit, one of the most used commands is println, which outputs its arguments to the screen with a new line at the end. The action of "printing" is a side effect because it changes the state of the world outside the program. Next, we will explore how side effects challenge the computational model we established in Chapter 2.

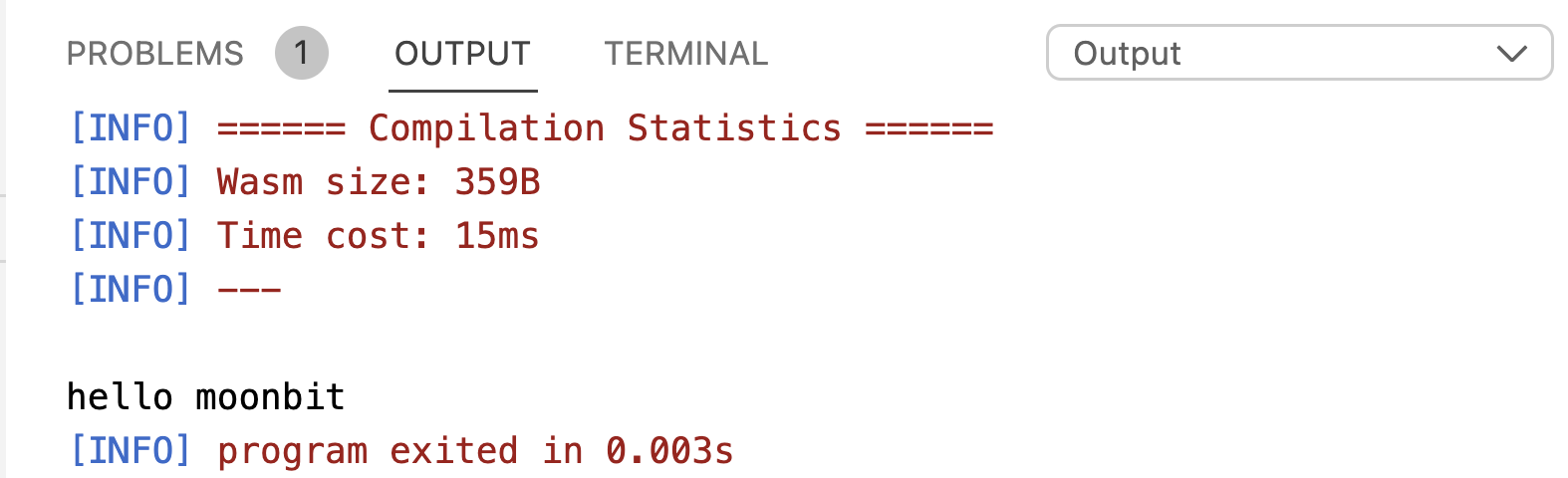

In the following example, the value assigned to x comes from an expression block, in which the println command is executed first, and then the result of the expression 1 + 1 is assigned to x. Finally, the value of z is the result of square(x), which is 4. In the whole process, println is executed only once.

fn square(x: Int) -> Int { x * x }

fn init {

let x: Int = {

println("hello moonbit") // Print once

1 + 1 // 2

}

let z: Int = square(x) // 4

}

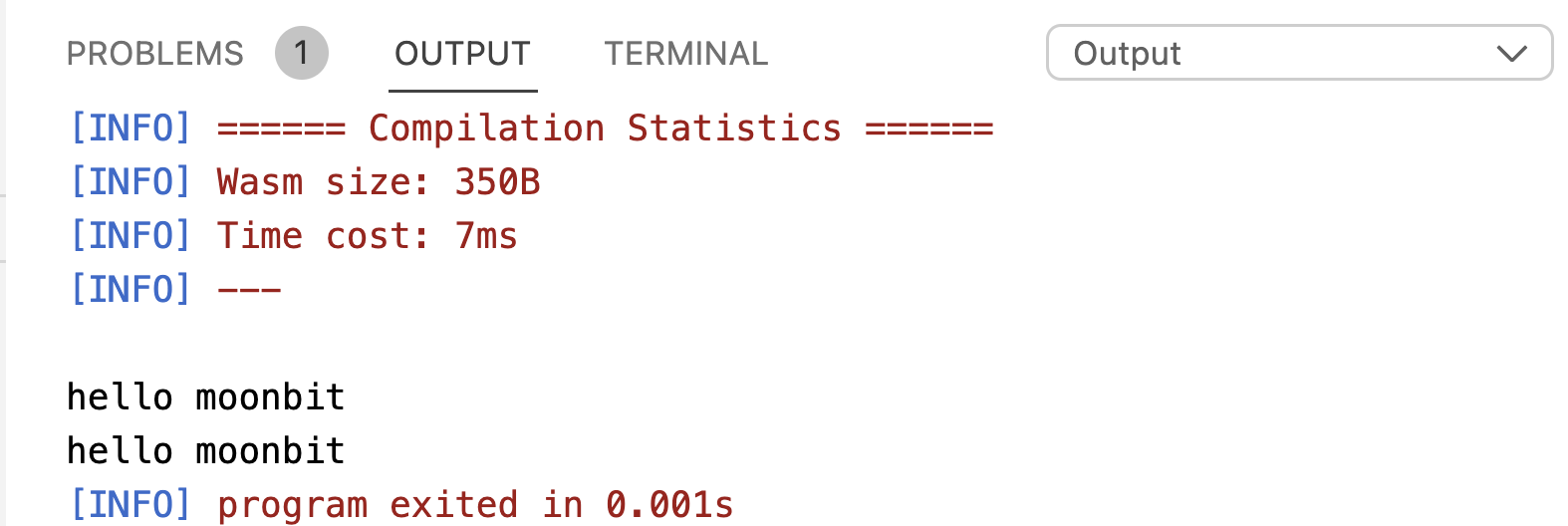

However, if we replace all occurrences of x and square with their definitions using the method introduced in Chapter 2, we will get the following program:

fn init {

let z: Int = {

println("hello moonbit"); // Print once

1 + 1 // 2

} * {

println("hello moonbit"); // Print twice

1 + 1 // 2

} // 4

}

In functional programming, the two programs should be equivalent, because they compute the same result. However, because of the side effect of println, the two programs behave differently: the former produces one line of output, while the latter produces two lines of output. It can be seen that side effects could destroy referential transparency and thus make it more difficult to reason about programs.

The Unit Type

In Chapter 2, we introduced the Unit type, but we did not clearly explain its usage at the time. Here, we can see that in imperative programming, commands like println are purely for side effects and do not have a return value. However, in MoonBit, commands are just a special sort of expression. Besides performing their side effects, they should also be able to be reduced to a value, which of course needs to have a certain type. In such cases, we use the Unit type, which consists of only one value () and is thus suitable for representing the absence of a meaningful return value, like a placeholder.

In particular, the let statement in MoonBit is essentially a command, and its type is also Unit. For example:

fn do_nothing() -> Unit {

let _x = 0 // The `let` statement is of type `Unit`

}

Mutable Variables

As we learned in Chapter 3, we can create mutable variables in MoonBit using let mut, and update the binding with the command <variable> = <expression>, whose type is also Unit. For example:

fn init {

let mut x = 1

x = 10 // The assignment operation is a command.

}

In Chapter 4, we learned about structs. In MoonBit, the fields of a struct are immutable by default, but mutable fields are also supported. To make a filed mutable, we need to mark it with mut. For example:

struct Ref[T] { mut val : T }

fn init {

let ref: Ref[Int] = { val: 1 } // `ref` itself is just a data binding

ref.val = 10 // We can modify the fields of the struct

println(ref.val.to_string()) // Output 10

}

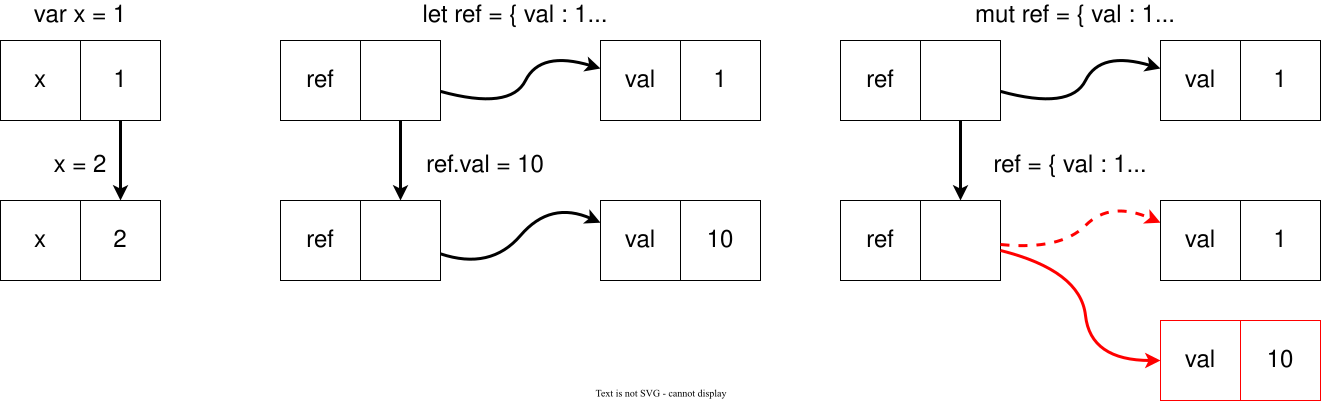

The distinction between mutable and immutable data is important because it affects how we think about the data. As shown in the following diagrams, for mutable data, we can think of identifiers as boxes that hold values.

- In the first diagram, when we modify a mutable variable, we are essentially updating the value stored in the box.

- In the second diagram, we use

letto bind the identifierrefto a struct. Thus, the box contains a reference to the struct. When we modify the value in the struct usingref, we are updating the value stored in the struct which it points to. The reference itself does not change because it still points to the same struct. - In the third diagram, when we define a mutable

refand modify it, we are creating a new box and updating the reference to point to the new box.

Aliases

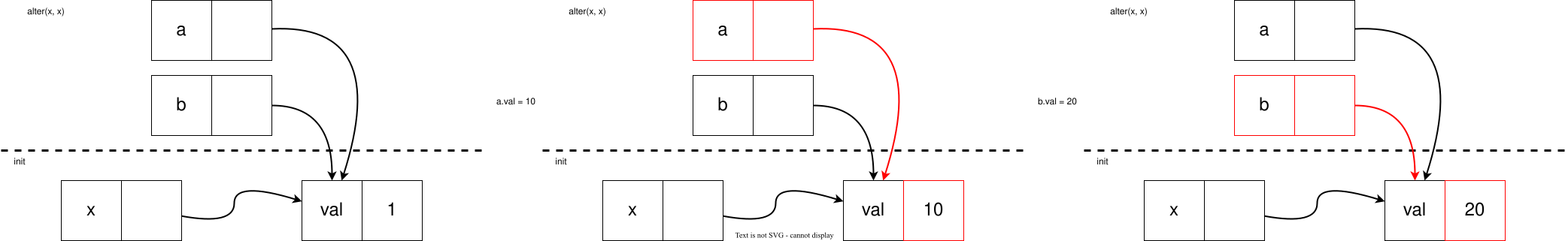

Multiple identifiers pointing to the same mutable data structure can be considered aliases, which need to be handled carefully.

In the following example, the alter function takes two mutable references to Ref structs, a and b, and modifies the val field of a to 10 and the val field of b to 20. When we call alter(x, x), we are essentially passing the same mutable reference, x, twice. As a result, the val field of x will be changed twice, as both a and b are just aliases referring to the same x reference.

fn alter(a: Ref[Int], b: Ref[Int]) -> Unit {

a.val = 10

b.val = 20

}

fn init {

let x: Ref[Int] = { val : 1 }

alter(x, x)

println(x.val.to_string()) // x.val will be changed twice

}

Loops

Loops are a way to repeat a block of code multiple times. In MoonBit, we can use a while loop to do this. We start by defining a loop variable, say i, and giving it an initial value. Then we check the condition defined in the while loop. If the condition is true, we execute the commands inside the while loop's body. This process repeats until the condition is no longer true, at which point the loop ends. To avoid an infinite loop, we need to update the loop variable inside the loop body.

fn init {

let mut i = 0

while i < 2 {

println("Output")

i += 1

} // Repeat output 2 times

}

For example, we might want to print the numbers from 0 to 1. We can do this with a loop that checks if i is less than 2. If it is, we print the current value of i, increment i by 1, and then repeat the process. The loop continues until i is no longer less than 2, and then we're done.

Loops and Recursion

Loops and recursions are equivalent. A loop is a set of instructions that we repeat until a certain condition is met, while recursion is a way of solving a problem by breaking it down into smaller, similar problems. In programming, we can often rewrite a loop as a recursive function and vice versa.

For example, let's consider calculating the Fibonacci sequence. We can do this with a loop that keeps track of the last two numbers and updates them as it goes. Alternatively, we can write a recursive function that calls itself with smaller numbers until it reaches the base cases (0 and 1).

// Loop form

fn init {

let mut i = 0

while i < 2 {

println("Hello!")

i = i + 1

}

}

// Recursive form

fn loop_(i: Int) -> Unit {

if i < 2 {

println("Hello!")

loop_(i + 1)

} else { () }

}

fn init {

loop_(0)

}

Controlling Loop Flows

Sometimes we want to control the flow of a loop more precisely. We might want to skip the rest of the current iteration or exit the loop entirely. In MoonBit, we can use break to exit a loop early or continue to skip the rest of the current iteration and move on to the next one.

For example, if we're printing numbers from 0 to 9, but we want to skip the number 3, we can use continue in the loop condition. If we want to stop the loop entirely when we reach 3, we can use break.

fn print_first_3_break() -> Unit {

let mut i = 0

while i < 10 {

i += 1

print(i)

println(" yes")

if i == 3 {

break // Skip from 3 onwards

} else {

println(i.to_string())

}

}

}

The excepted output is

1 yes

2 yes

But if we change break to continue

fn print_first_3_continue() -> Unit {

let mut i = 0

while i < 10 {

i += 1

print(i)

println(" yes")

if i == 3 {

continue // go into the next iteration

} else {

println(i.to_string())

}

}

}

The excepted output is

1 yes

2 yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

yes

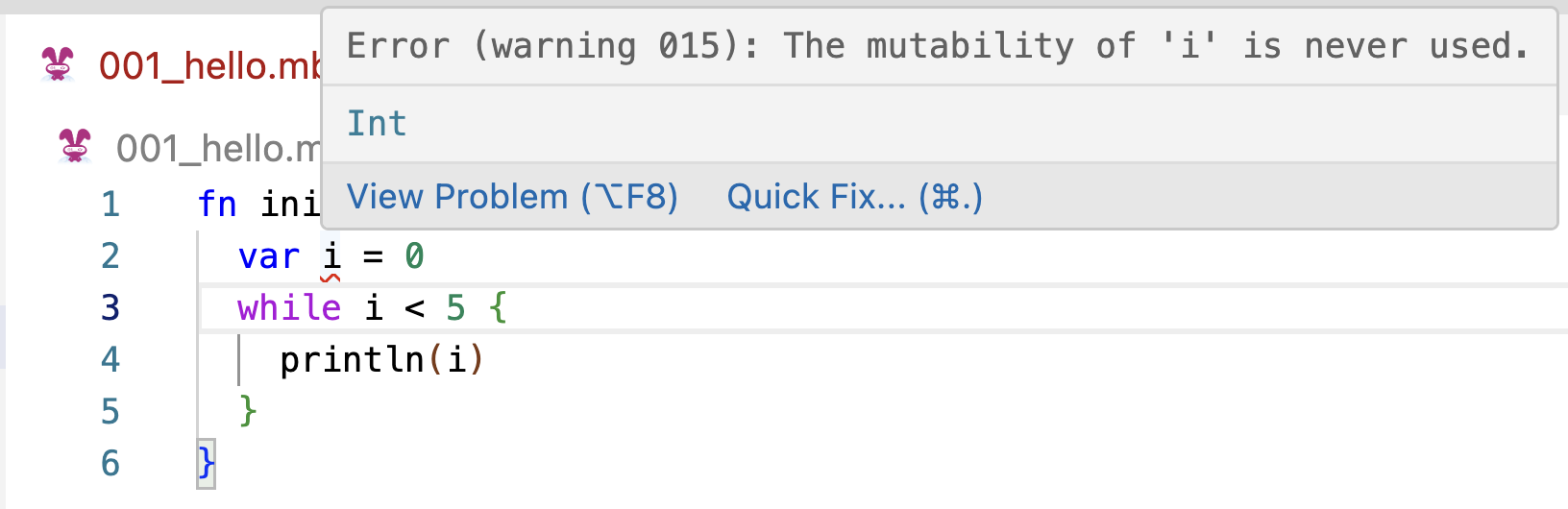

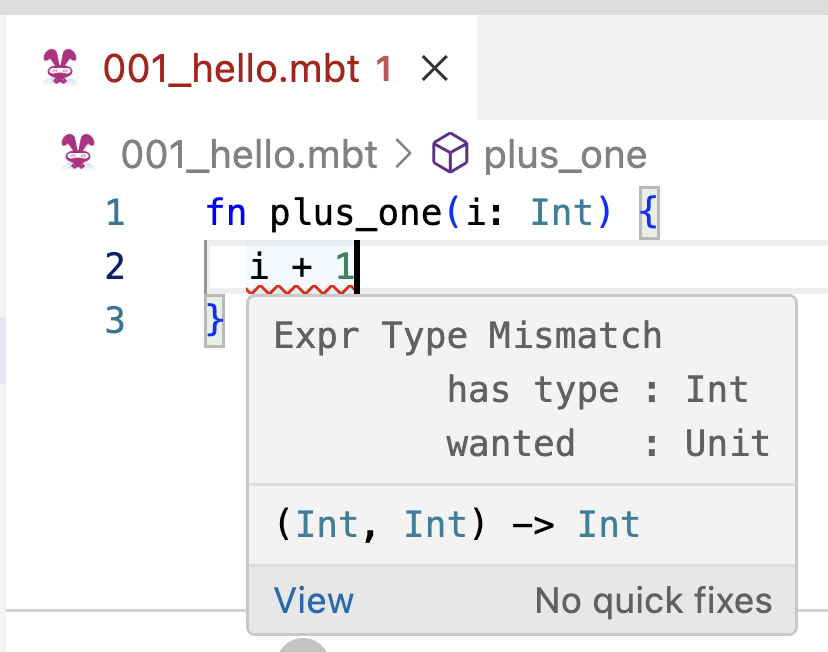

Code Checking and Debugging

In order to avoid errors, we need to check our code. However, this work does not need to be done entirely by us, the MoonBit extension on VS Code can help us to some extent. Here are some examples:

- If a mutable variable has not been modified, MoonBit extension will issue a warning, which can help us catch mistakes like forgetting to update a loop counter.

- It also checks whether the return value of a function matches the declared return type, which helps us avoid typing errors.

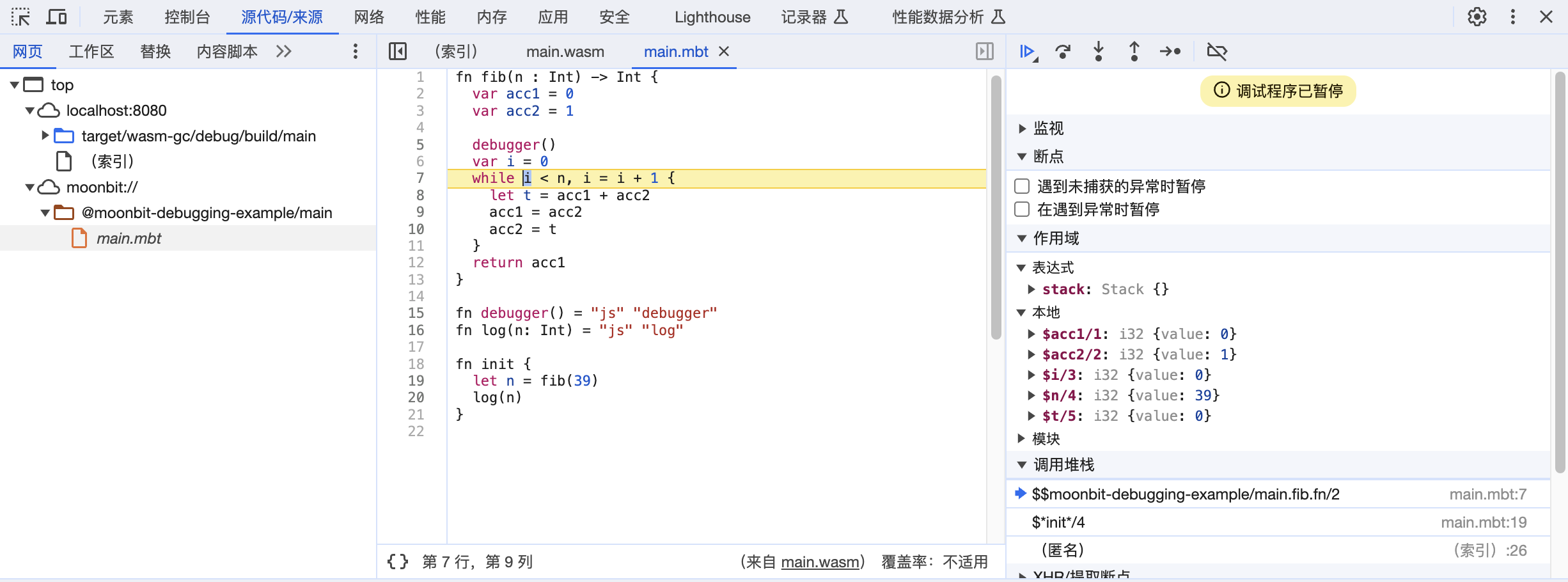

Sometimes, even our code passes the checking by our naked eyes and MoonBit extension, our code may still not behave as expected, which means there are bugs in our code. In that case, we need to debug our code. MoonBit's debugger is a tool that helps you debug your code by showing you what's happening inside your program as it runs. You can pause the program at any point, look at the values of variables, and step through the code one line at a time. This is incredibly useful for understanding complex behavior and fixing bugs.

Trade-Offs of Mutable vs Immutable Data

Although mutable data challenges the functional computational model we established before and may introduce some potential problems, it is still widely used in various scenarios. If we want to directly manipulate the external environment, e.g., hardware, it is better to use mutable data structures. When random access is needed, an mutable array typically performs better than a immutable list. Mutable data also makes it easier for us to construct complex data structures, such as graphs. In addition, in-place modification of mutable data can better utilize memory space, as it does not introduce additional space consumption.

Mutable data is not always in conflict with referential transparency. In the following example, we use a while loop and some mutable variables to calculate the nth term in the Fibonacci sequence. However, we can still safely replace any occurrence of fib_mut with its final result, since it does not produce any side effects.

fn fib_mut(n: Int) -> Int {

let mut acc1 = 0; let mut acc2 = 1; let mut i = 0

while i < n {

let t = acc1 + acc2

acc1 = acc2; acc2 = t

i = i + 1

}

acc1

}

Summary

In this chapter, we've explored the basics of imperative programming. We've learned about using commands to tell the computer what to do, variables to store values, and loops to repeat actions. Imperative programming is inherently different from functional programming, and it's important to understand the trade-offs between the two. By understanding these concepts, we can choose the right tools for the job and write programs that are both effective and easy to understand.